Planning Under Way for Water & Natural Resources Tour

The date is still months away, but not too early to begin thinking about the annual Water and Natural Resources Tour organized by the Nebraska Water Center and The Central Nebraska Public Power and Irrigation District.

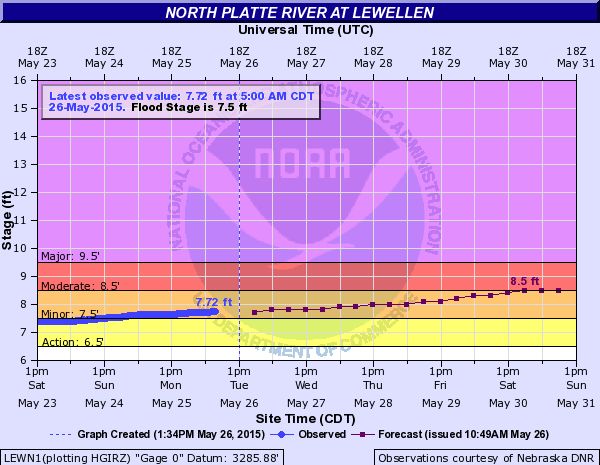

This year’s tour will take place on June 27-29. The destination will be Nebraska’s west-central Platte River Basin between Elm Creek and Lake McConaughy.

“This is a critical stretch of the Platte River that has many-faceted and far-reaching impacts on all Nebraskans,” said Steve Ress communicator for the Nebraska Water Center, which is part of the Robert B. Daugherty Water for Food Global Institute. “It is tremendously important for agriculture, Nebraska’s economy, recreation, hydropower production, fish and wildlife habitat and many other interests.”

The Water and Natural Resources Tour began more than 40 years ago as an idea of then UNL Chancellor D.B. “Woody” Varner. What was originally an irrigation tour has evolved over the years into a broad investigation of many water and environmental topics relevant to Nebraska.

Tentative stops and topics on the tour include an organic farming operation; facilities related to Central’s hydro-irrigation project, including Kingsley Dam and Lake McConaughy; the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission’s Water Interpretive Center at Lake McConaughy; projects underway by Platte Basin Natural Resources Districts; the Frito-Lay corn Handling Facility at Gothenburg and Monsanto’s Water Utilization Learning Center at Gothenburg; UNL’s West Central Research and Extension Center near North Platte for discussion of new cropping and irrigation technology research, a stop at a Platte River Recovery Implementation Program site; the Nebraska Public Power District’s Gerald Gentleman Station near Sutherland, and more. Planning is underway to end the tour with a kayak trip on a stretch of Central’s Supply Canal.

“Anyone who is interested in water resources, be they producers, researchers, or work in the water resources field, is welcome to attend,” said Central’s Public Relations Coordinator Jeff Buettner. “Our agenda will be packed with interesting topics and our goal is to present a broad overview of why this stretch of the Platte River is so important to Nebraska for many different reasons.”

Registration information for the tour will be announced soon. The latest tour information will be online at watercenter.unl.edu. Participation will be limited to the first 55 registrations.