A small aquatic species, not much bigger than your thumbnail, poses a threat to Nebraska’s lakes, reservoirs and associated power-generating facilities. Once established, the critters are extremely difficult and expensive to remove.

The creature is the zebra mussels (and their relative, the quagga mussel). But Nebraska is not without defenses. As the Memorial Day weekend — and the summer recreation season — approaches, boaters and recreation-seekers can help by simply cleaning, draining and drying a boat, trailer and related equipment to help prevent the invasion.

The zebra mussel has caused enormous problems in other parts of the country and has been detected in Nebraska in a lake at Offutt Air Force Base and on a dock on the South Dakota side of Lewis & Clark Lake. Evidence of zebra mussels was also discovered on a boat and trailer at Harlan County Lake, although the specimens had died before the boat entered the water. Whether it spreads to other lakes and rivers depends to a large degree on the public’s vigilance. The mussels are one of many invasive species found in various lakes and rivers that can cause damage to boat motors and clog cooling water intakes at power plants.

Pipes clogged by accumulation of quagga mussels.

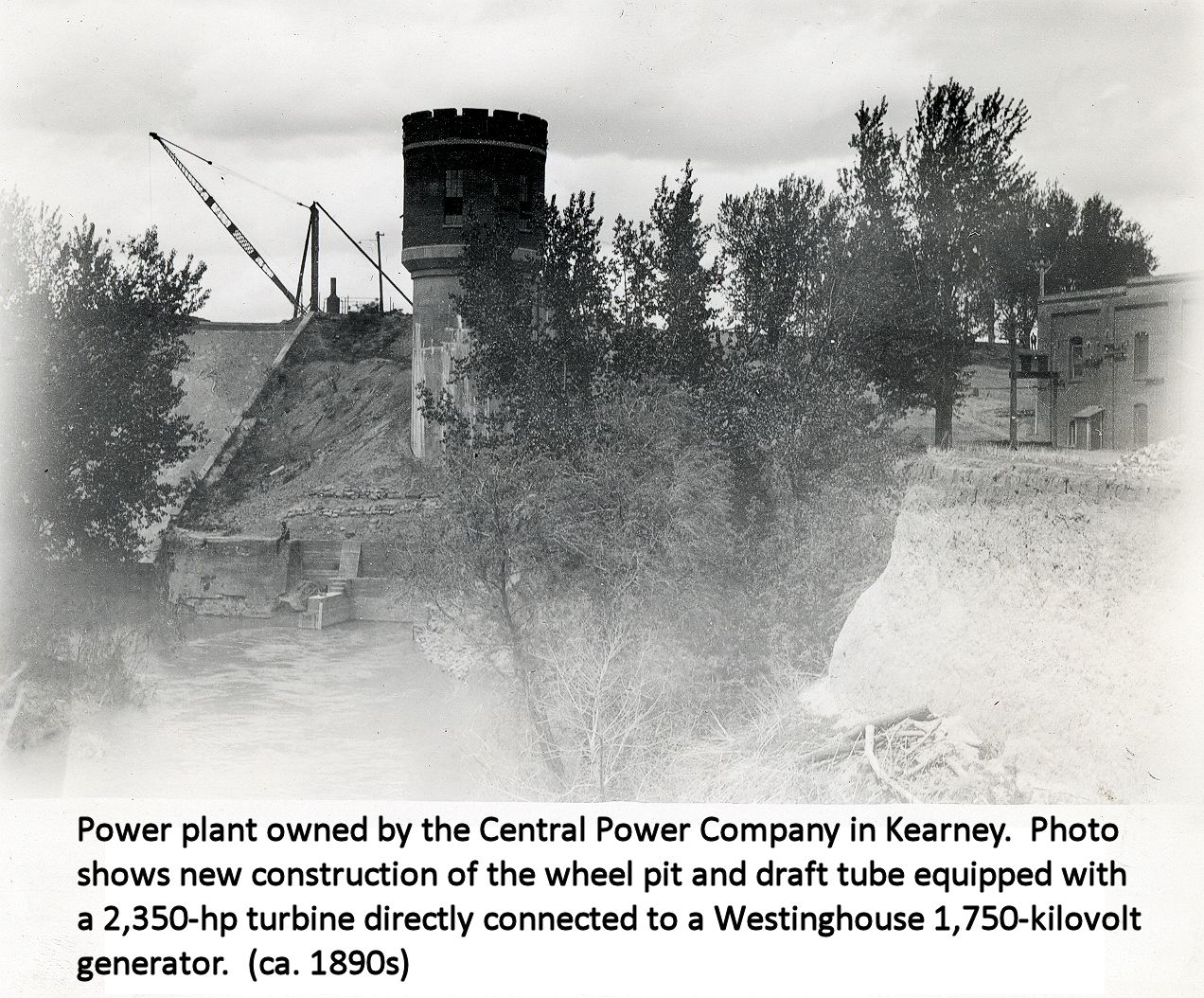

The Central Nebraska Public Power and Irrigation District uses water to generate electricity at the Kingsley Hydroplant at Lake McConaughy and also at three hydroplants along the Supply Canal between North Platte and Lexington. In addition, the Nebraska Public Power District uses water from Lake McConaughy to cool equipment at Gerald Gentleman Station near Sutherland, and to produce power at the North Platte Hydroelectric Plant. Preventing aquatic invasive species from fouling intake pipes and other equipment is important to continuing Nebraska’s ability to provide low cost, reliable electricity.

“We’ve seen the devastation that zebra mussels have done to water bodies in other states,” said Central Senior Biologist Mark Peyton. “They dramatically change the fishery and natural balance of the lake or river. What’s more, when they are in a system like the Platte River, it would be next to impossible to prevent them from infesting all the other water bodies associated with that system.

“Once a body of water is contaminated, monetary resources that could be used to improve and enhance recreational opportunities and wildlife value at the lakes are used instead to clean up and contain the mussels. All in all, the mussels simply are not good for the system or for the people using the system. We hope that people who use the lakes in Nebraska don’t become complacent about the threat because it’s out there, it’s real.”

A freshwater mollusk native to eastern Europe and western Asia, the zebra mussel — so named for its striped shell — was first detected in North America in 1988 in Lake St. Clair, a small lake between Lake Huron and Lake Erie. The first specimens probably arrived in the ballast water of ships that sailed from a freshwater port in Europe. It has since spread throughout the Great lakes region and to river systems in the Midwest, including the Ohio, Illinois, Arkansas, and Mississippi rivers.

How can such a small mollusk create such problems? First, they reproduce prolifically. A single female, which has a life span of up to five years, can lay more than a million eggs during a single spawning season. Second, the mussels anchor themselves to hard surfaces in huge numbers.

Water intake pipes at factories, water treatment plants, and power plants have been clogged by the buildup of mussels, requiring difficult and expensive removal. Beyond industry, zebra mussels can infest boat hulls and motors, docks, lifts and any other structure in the water. The shells of dead mussels can accumulate in great quantities on swimming beaches, the sharp edges posing a threat to swimmers’ feet.

In addition, because they feed by filtering algae and plankton from the water, they can disrupt the food chain at its base.

A relative of the zebra mussel, the quagga mussel, has been discovered at Julesburg Reservoir in the South Platte Basin, less than 50 miles from Lake McConaughy. The quagga poses the same threat to industry and recreation as the zebra mussel and has been found in many western lakes. Nationwide, the economic impact of the mussels comes to billions of dollars.

Karie Decker, formerly the coordinator for the Nebraska Invasive Species Project and now an assistant division administrator for the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission’s Wildlife Division, said, “Everyone who uses our lakes for any reason, be it recreation, irrigation, or power production, has a stake in preventing the spread of these species. Quite literally, they can ruin a lake.”

She said there would be no way to eradicate the mussels if they gained a foothold in Lake McConaughy.

“We could only hope to contain them and even that would be expensive for Nebraska,” she said.

At the root of the state’s effort to educate the public about the threat posed by the mussels is the slogan, “CLEAN. DRAIN. DRY.” Lake visitors are urged to clean, drain and dry any watercraft and recreational equipment before putting them into the water.

“Inadvertent human transport is the main pathway for introducing the mussels to other lakes,” Decker said. “We want to make sure people aren’t transporting water that may contain larvae from one lake to another in boats, live wells, bait buckets, waders, or even vegetation attached to boat trailers.”

Decker said it doesn’t take long to inspect boats. The more difficult task, she said, is simply making people aware of the need to do so and getting them to follow through with regular inspections.

The public is the only line of defense and Nebraska needs help to repel the invader. For more information about the invasive mussels, visit the Nebraska Invasive Species Project’s web site at http://snr.unl.edu/invasives.

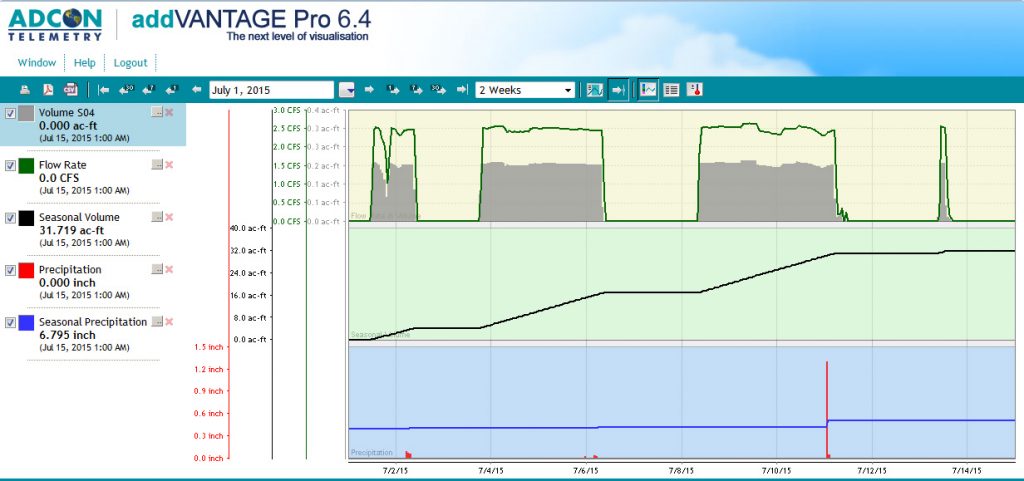

The outcome of precision management is expected to be high yields with minimum use of irrigation water. It is possible that an irrigation event can be saved at the beginning or end of the season or both once the producer has reliable information on hand to make those decisions.

The outcome of precision management is expected to be high yields with minimum use of irrigation water. It is possible that an irrigation event can be saved at the beginning or end of the season or both once the producer has reliable information on hand to make those decisions.