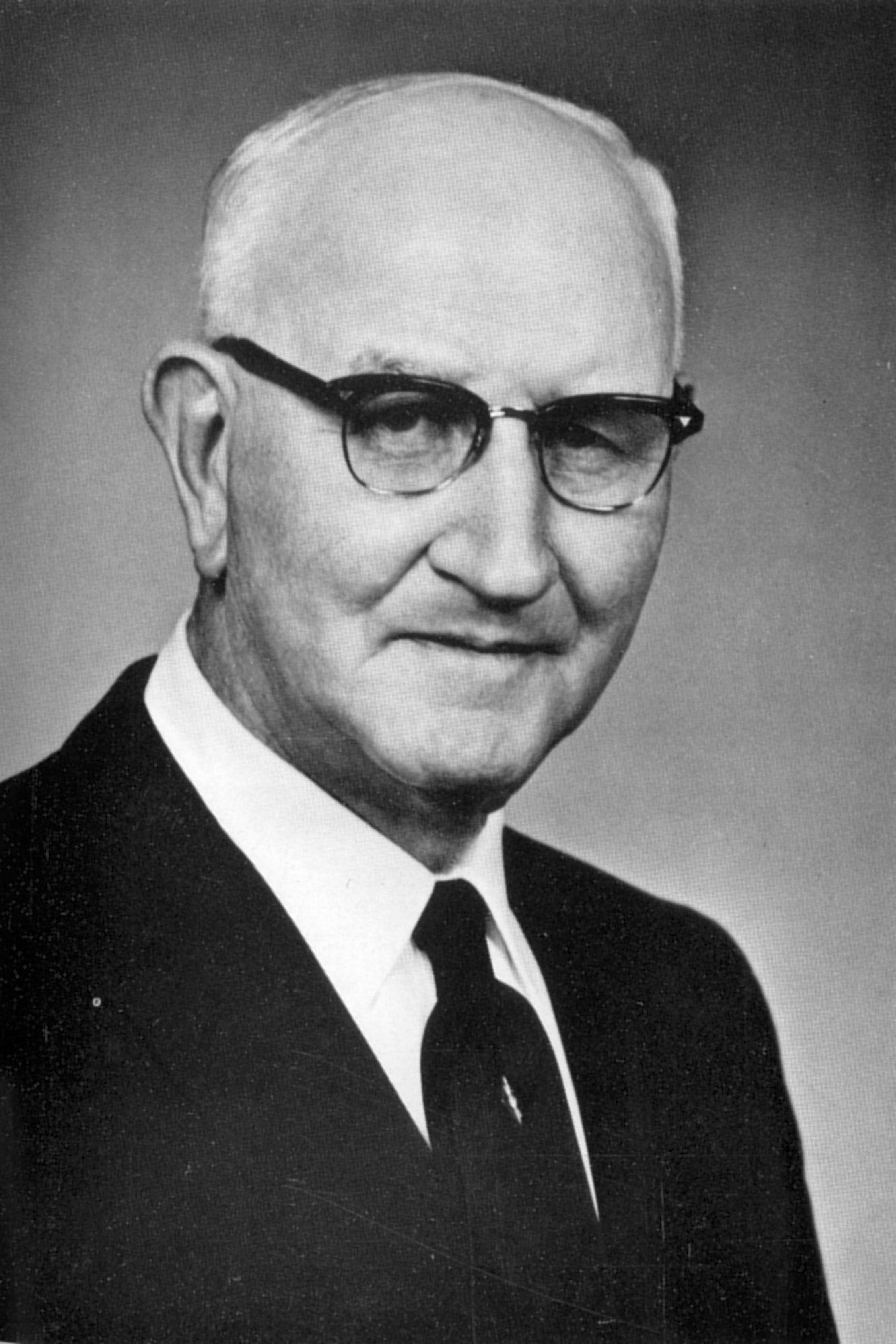

George E. Johnson, irrigation and power pioneer, nominated for Nebraska Hall of Fame

Author’s note: The following information was submitted to the Nebraska State Hall of Fame in the form of a nomination of George E. Johnson for induction into the Hall. While I debated whether to shorten the information for inclusion in this blog article, in the end I determined that doing so would be an injustice to Mr. Johnson, his work to make Nebraska a better place, and his accomplishments throughout his career in engineering. So, apologies to readers for the length of the entry, but — for those interested in this kind of information — it makes for fascinating reading about one of the state’s most accomplished citizens. — JB

Biographical information and narrative of his accomplishments and impact on the State of Nebraska

George Edward Johnson (March 17, 1885 – Oct. 29, 1967) was born at Wymore, Neb. He received his education in the Wymore schools until age 10 when he left home to train as an apprentice in his uncle’s foundry in Nebraska City. He became a fully qualified iron molder and machinist by the time he graduated from high school at the age of 15. By that time he had become enamored with machines and mechanics and particularly with electricity. Against his family’s wishes, Johnson enrolled at the Armour Institute in Chicago, where he received B.S. Degrees in civil engineering in 1905 and electrical engineering in 1906. He worked as a consulting engineer in several states and countries, but most of his efforts over the rest of his life were concentrated in Nebraska He applied for and was appointed state engineer in 1915 and served in that capacity until 1923. During this time, he first became aware of efforts to build the Central Nebraska Public Power and Irrigation District’s (CNPPID) hydro-irrigation project. He later served as chief engineer and general manager for CNPPID from 1935 to 1947, when he left the District to work in Argentina for three years. He returned to CNPPID in 1952 as chief engineer and later as a consulting engineer of the District’s Hydro Division and manager of the Steam Generating Division during and after construction of the Canaday Steam Plant (a natural-gas fueled plant located southeast of Lexington). He resigned from the District in January 1959, although he remained active as a consulting engineer for the District until fully retiring in 1964. He died in Hastings in 1967 at the age of 82 and was interred at Parkview Cemetery in Hastings.

Johnson is perhaps best known for his work with CNPPID before, during and after the construction of the hydro-irrigation project, known then as the “Tri-County Project,” which is anchored by Kingsley Dam and Lake McConaughy. However, he enjoyed a long and eventful career that included many other large-scale public projects in Nebraska, as well as civil and electrical engineering projects in neighboring states and in South America. He was one of the most important figures in the development of Nebraska’s public power model for providing electricity throughout the state. He served as Nebraska’s state engineer during the early part of the 20th century for the State Board of Irrigation, Highways and Drainage (an early predecessor of today’s Department of Natural Resources). While serving as state engineer, the board was renamed the Department of Public Works in 1919 and was then composed of two bureaus and one headquarters division: the Bureau of Roads and Bridges; the Bureau of Irrigation, Water Power, and Drainage; and the Motor Vehicle Records Division.

From the time Johnson started working to support the Tri-County Project in 1915 until formerly being hired in 1935, all of his time and expenses related to the project were provided without compensation, except for expenses incurred during to two trips to Washington, D.C.

Johnson’s Role with The Central Nebraska Public Power and Irrigation District

Johnson was in his first month in the state engineer’s office in April 1915 when he first learned of efforts to build an irrigation project in south-central Nebraska. George P. Kingsley and C.W. McConaughy, two early advocates of the irrigation project, visited Johnson in his Lincoln office to discuss their efforts to secure financing and approval for what would become known as the “Tri-County Project.”

As originally proposed, the project was quite simple. Water would be diverted from the Platte River into canals that would lead to area farm fields. The crop land would be flooded before and after the summer growing season when there was typically excess water in the river. Water would not be provided during the growing season; instead crops would be able to draw upon “sub-soil moisture” during the summer. Storage reservoirs were not proposed as part of the original plan. Johnson immediately recognized that such a project would never be approved or successful without plans for storage. By May he had drawn up and submitted plans to Kingsley that provided for two storage reservoirs as well as two hydroelectric plants.

Over the ensuing years, Johnson, Kingsley, McConaughy and other promoters of the irrigation project made many trips to Washington, D.C. to plead their case and to seek a federal study to correct the conclusions from a 1915 government survey that said the project was infeasible. Initially Johnson and the other Tri-County supporters attempted to convince the Bureau of Reclamation to provide the funds for the new study and to build the project as a Reclamation project.

In 1923, Johnson resigned his position as state engineer to devote more time to gaining approval for the Tri-County Project. He later wrote, “Ever since I was state engineer in 1915, I have been concerned with the effort to conserve our most valuable resource, water. Without water, the land is unproductive. With water, crops will flourish. Full utilization of the water flowing through the state for irrigation and electrical power is vital to our economy.”

The Tri-County delegation finally secured a resolution from Congress directing the Reclamation Service to conduct another survey and prepare a report on the feasibility of the project. In addition to Reclamation dollars, funds were raised by the Tri-County Supplemental Water Association by agreement with Reclamation to supplement the federal contribution. The “Smith Report,” as it became known, was favorable to the project, but a long road still lay ahead. Five different designs for the irrigation project were proposed; the fifth was a plan that called for a complete project with two reservoirs on Plum Creek impounding a total of 509,000 acre-feet of water, a hydroelectric station below each reservoir, transmission facilities for the power, and approximately 500,000 irrigated acres.

While the feasibility study was underway, Johnson and Dr. George Condra, director of the Conservation and Survey Division (CSD) at the University of Nebraska from 1921 to 1954, were evaluating several alternative sites for a reservoir. They concluded that the most suitable location was near Cedar Point on the North Platte River, the site where Kingsley Dam would eventually be constructed. But for the time being, these alternative sites were set aside.

The rest of the 1920s and early ‘30s brought one disappointment after another to Johnson, Kingsley, McConaughy and other irrigation supporters.

Meanwhile, using as a template a bill that he had drafted in Missouri to provide for the organization of municipal water and sewer districts, Johnson drafted what would become known as Senate File 310 for the 1933 session of the Nebraska Legislature. The bill provided for the creation of public power and irrigation districts in Nebraska and was eventually passed by the Legislature, despite vigorous opposition from private power interests, and signed into law.

Johnson and the other Tri-County supporters continued to press on toward the vision they shared for the future of Nebraska. On July 24, 1933, the Nebraska Department of Roads and Irrigation approved a petition to organize the Central Nebraska Public Power and Irrigation District, although many hurdles remained to be cleared before the project became a reality. The remainder of the year was spent preparing an application for funds to the newly created Public Works Administration (PWA). The state PWA board approved the application in November and sent it to Washington.

It was too late. PWA funds had been depleted and Tri-County supporters were told they would have to wait for the next session of Congress.

However, while Tri-County struggled to gain a foothold, another irrigation project was trying to secure a Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) loan. The Platte Valley Public Power and Irrigation District (also known as the Sutherland Project) and the Tri-County Project thus became competitors for funds as well as for Platte River water rights. The legal and political battles that followed were frequent and intense.

The Sutherland Project was given final state approval in June 1933 and its application was transferred from the RFC to the PWA. It was one step ahead of the Tri-County Project. However, Tri-County had already established a prior claim for a water right, while the Sutherland Project had yet to secure the necessary water rights. The main protest from Sutherland was that there would not be enough water in the Platte River for two irrigation projects. Sutherland repeatedly challenged Tri-County’s water rights, but to no avail.

Tri-County and Sutherland finally reached a compromise water rights agreement on Jan. 13, 1934, which resulted in water rights for both districts. Meanwhile, the PWA continued to study the Tri-County project and had given preliminary approval to the proposal, although there was some doubt about the project’s power generation claims. The PWA engineers also questioned if there would be a sufficient market in Nebraska for the electricity. Johnson went to Washington, rented a hotel room by the month and prepared to stay as long as necessary to convince the PWA that their concerns were unfounded.

During this time, to help answer the PWA questions, a Tri-County power market survey completed in February, 1934 showed 24 communities interested in Tri-County power.

While Tri-County leaders continually battled opposition from supporters of the Sutherland project and the City of Grand Island, opposition sprung up in a surprising place: the area which was to receive the benefits of the irrigation water, particularly Phelps County. Many farmers were skeptical that the project was needed in the first place. They also feared that the project would be too expensive, that it would bring about higher taxes and that the project would never be able to pay for itself. Project opponents, particularly private power companies, were quick to instigate and play up these fears.

Indeed, with rainfall generally plentiful at the time, it was difficult to make a case for an irrigation project. However, the 1930s ushered in a period of drought and depression that gripped the nation, circumstances that may have been a boon to Tri-County supporters. They pointed to withering corn fields and dusty topsoil being blown into drifts and said, in effect, “This could all be prevented; the project could offset the effects of drought and help this area prosper in the face of drought.”

Another important development occurred in April 1934. PWA engineers visiting Nebraska suggested that a dam and reservoir be built on the North Platte River near Keystone – at the site that Johnson and Dr. Condra had determined to be ideal in 1922 — instead of the two Plum Creek Reservoirs proposed in Tri-County’s plan. The dam would store enough water to supply the Sutherland project, the Tri-County project and, said the engineers, some future irrigation projects.

Tri-County immediately filed for storage rights behind the proposed dam.

The Keystone (Kingsley) Dam proposal probably saved the Tri-County project. The PWA had decided to reject the project, but the project was transferred to a special review board which endorsed it with the new dam site. But an obstacle remained: the PWA still had no funds to provide.

Regardless of the review board’s assessment, the PWA’s engineering and finance divisions had rejected the project because they believed that costs would far exceed submitted estimates and the power generation proposal was “technically unsound.” Johnson submitted a new application with revised cost estimates to the PWA on Jan. 23, 1935. The board recommended that a way be found to avoid duplication of the power market served by Sutherland.

Johnson’s application on Tri-County’s behalf was again revised and submitted to the PWA Power Division on Aug. 1, 1935. It included a diversion dam near Keystone, the Plum Creek reservoirs and power plants. The cost was estimated at $33.6 million.

Three weeks later, Johnson submitted Tri-County’s final application to the PWA. In an effort to contain costs, the Keystone reservoir proposal had been dropped and the size of the three power plants had been reduced. In addition, plans to build the Plum Creek reservoirs were resurrected.

The long-awaited approval of the Tri-County project came on Aug. 24, 1935. The power division of the PWA recommended approval of a $20 million loan to the project after Tri-County’s water rights were validated.

As approved, the project would bring water to 305,000 acres from just west of Bertrand in Gosper County to 10 miles east of Minden in Kearney County. Another 144,000 acres in Adams County would also receive water.

Celebrations erupted throughout south-central Nebraska when the news was made known on Sept. 26, 1935. A parade, complete with bands and floats, was staged in Hastings as tribute was paid to Tri-County’s leaders. The people of Adams County had been among the project’s staunchest supporters, but a turn of events denied them the water for which they had worked so hard. The Sutherland project continued its opposition even after President Franklin D. Roosevelt officially signed the approval for the $20 million loan on Sept. 18, 1935. In addition, Nebraska’s six large private power companies opposed the Tri-County loan by bringing suit against the PWA.

The opposition from the Sutherland supporters and the power companies resulted in significant changes to the original water claims, the most important of which was the PWA’s recommendation in November 1935 that a large reservoir on the North Platte River be constructed after all, instead of the Plum Creek reservoirs.

Tri-County leaders accepted the PWA’s recommendation and the two Plum Creek Reservoirs were dropped in favor of one large reservoir at the Keystone site. Johnson also drew up plans that would increase electrical generating capacity.

Opponents of the project tried one more time to stop its construction, filing an appeal in the Nebraska Supreme Court in December 1935 in opposition to the granting of Tri-County’s water rights.

The court’s ruling in the case came on June 29, 1936. Although the court refused to reject the water rights outright, it did rule that the project could not divert water out of the Platte River watershed, thereby eliminating more than half of the lands which were to receive irrigation water, including all of the acres in Adams County. Repeated attempts by Tri-County leaders to have the acres reinstated were unsuccessful. In subsequent years, several legislative attempts to revise Nebraska’s irrigation laws to permit trans-basin diversions also failed before the Supreme Court ruling was overturned in 1980 and such diversions legalized (Little Blue NRD v. Lower Platte NRD).

Construction of the Tri-County project began on March 13, 1936 with ground-breaking ceremonies on the Phelps County Canal, followed by simultaneous work on Kingsley Dam, the North Platte Diversion Dam, a 76-mile-long Supply Canal, three downstream hydroelectric plants and the irrigation canals and laterals. Most of the construction on the project’s works was finished during 1940 and water began flowing into the Supply Canal in November 1940. The first power was generated at the Jeffrey plant on Jan. 5, 1941. Johnson looked over U.S. Sen. George Norris’ (a steadfast supporter of the project from the beginning) shoulder as the senator pulled the switch to bring the hydroplant on-line for the first time.

Kingsley Dam was closed shortly thereafter allowing storage in Lake McConaughy to begin. The dam was officially dedicated at ceremonies on July 22, 1941 and the first irrigation water from Lake McConaughy was delivered that same year. Irrigation delivery and related operations began in earnest in 1942 and the project was officially completed in 1943.

As the project’s major facilities were completed, they had to be named. In recognition of Johnson’s tireless efforts to see the project through to completion, Tri-County’s board of directors decreed that two hydroplants – Johnson No. 1 and Johnson No. 2 – and the regulating reservoir above them (Johnson Lake) should be named in his honor.

The total cost of the Project was $43 million, paid by a $19 million PWA grant and a $24 million federal loan (the federal debt was paid off when the loan was refinanced in 1972; the refinanced portion of the debt was paid off in 1995). The Depression-era construction project provided jobs to more than 1,500 people, but it was not simply a “make-work” project. It was the culmination of many years of planning and hard work by George Johnson, Fred Kingsley, Charles McConaughy, Sen. Norris and many others. It was the realization of the hopes and dreams of a group of irrigation pioneers who foresaw the prosperity irrigation water would bring to south-central Nebraska.

(Note: Research into media accounts of the development and construction of the “Tri-County Project,” which was the subject of many headlines in newspapers across the state in the 1930s and ‘40s, frequently mentioned Johnson as the chief engineer of the project, but his significant role was played out mostly behind the scenes. Johnson was not a “self-promoter,” rather he was an engineer who engaged in the physical and technical aspects of a project’s construction, whether it was the hydro-irrigation project, a plant to convert surplus grain to fuel, or military air bases in the state. That said, when necessary, he could assume the role of a lobbyist. In fact, a contemporary once called him “the slickest lobbyist in Washington.” Johnson disputed this designation by saying, “I did not see myself that way. True, I was lobbying to bring industries to the State of Nebraska. However, my methods were successful not because I was “slick,” but because I used basic engineering methods. I did not present “argument,” instead I marshaled the facts, as I would in an engineering report, so that the conclusion was almost inevitable considering the facts presented. Then, I always saw that these facts reached the right people at the right time. In these efforts, I was greatly aided by Senator Norris and his staff.”)

Early Career

Johnson’s early career, between graduation from the Armour Institute in 1906 and 1915 when he was appointed state engineer, was an eclectic mix of projects on which he honed his civil and electrical engineering skills.

He first worked in the electrical department at Swift’s Packing Co., in St. Joseph, Mo., then at the Columbian Electrical Co., designing power plants and distribution systems for cities and towns that were customers of the company.

In 1907, he worked on his own as a consulting engineer in Holton, Kan., where he designed and supervised the construction of an electrical generating plant and distribution system and a water and sewer system for the town.

Two years later, he moved to Sabetha, Kan., where he led similar water and power projects in addition to laying out a paved road system in the town. He also designed a power transmission line system from Sabetha to nearby small towns. Finally he designed and supervised the installation of a steam heating system, using the exhaust steam from the newly constructed power plant to heat buildings in the town’s business district.

In 1911, Johnson took his skills to Falls City, Neb., where he was involved with expanding the power and water system for the town. He also laid out plans for construction of a new sewer system and paving the community’s streets.

It was during this period that Johnson first encountered opposition from private power companies to his work to improve the water supply and sewer systems and electrical service in Horton, Kan. He later saw similar opposition in Atcheson, Kan., where the private power company owners perceived his work as a threat to their business. He implemented a process in Horton through which bonds were issued and, after the citizens voted to issue the bonds, the city took over the properties for water and power. He repeated this formula in Atcheson, despite interference with his efforts from the private power companies.

From that time on, firm in his belief that no one should realize excessive profits from the sale of such essentials as power and water, Johnson devoted virtually all of his work to public service, often times working without remuneration when he felt such an arrangement was necessary.

State Highway System

Johnson decided to pursue the position of state engineer in 1915. World War I had interfered with most municipal engineering work due to higher bond rates that made it difficult for municipalities to secure favorable financing for public projects. He was appointed to the position from among 14 other candidates and was reappointed in July 1916 by Gov. Keith Neville, Attorney General Willis Reed, and Land Commissioner Grant Shumway, who comprised the State Board of Irrigation, Highways and Drainage.

Also in July 1916, the first Federal Aid Road Bill was passed by Congress to make allotments to the states to construct interconnected highways between the states. Working with Deputy State Engineer Roy Cochrane, the federal government and county commissioners in several counties, they planned the routes for the State Highway System. The United States entered WWI in 1917, and Cochrane left his position with the state to join the Army as a captain and embarked for France. By that time, much of the work to lay out the highway system had been done, including field engineering, plans and specifications, but the actual awarding of contracts was delayed until after the war ended. Shortly thereafter, the state began to award contracts, a process that was in high gear over a period of several months. During this process, Johnson was instrumental in developing the state-federal dollar matching program for highways, which later became standard across the nation.

At the time, Johnson was a member of the executive committee of the American Association of State Highway Officials and a member of the Federal Highway Advisory Board. After the war ended, only $75 million had been allotted for highway construction across the United States. Johnson and the heads of the other highway departments convinced President Woodrow Wilson that another $200 million would be sufficient to begin awarding contracts for construction, which at the same time, would help alleviate a severe unemployment issue.

By the end of his fourth two-year term as state engineer in 1923, more than 3,000 miles of highways had been improved and the state highway department had been expanded to employ more than 600 people. The State Highway System in Nebraska at the time consisted of about 6,500 miles of roads.

Johnson worked with Nebraska county officials to set up a system so that roads were laid out beginning at the county seats and extended out to the county lines on the north, south, east and west. This was necessary to convince the rural members of the Legislature (who were in the majority at the time) that road improvements would also benefit farmers. He would later write that Nebraska’s system, as created, generally carried more farm traffic per mile than any roads in the country.

After acquiring surplus equipment from the Army, the roads department set about grading operations in preparation for the construction of gravel roads, a vast improvement over the dirt roads they were replacing. Johnson worked to secure equipment to develop both dry and wet gravel pits and began the program for graveling roads. Johnson worked with Dr. George Condra to develop a process to mix and spread the gravel in different sections, according to local soil types. Johnson later noted that the same method was used up through at least the 1960s.

When Johnson became state engineer in 1915, automobiles were rare and roads on which they could travel without difficulty even more rare. By the time he left the state engineer’s office in 1923, most of the state had come to rely on the automobile in one way or another. Traveling by horse and buggy had become a thing of the past, the state had a functional road and highway system, and the State Highway Department had been created. Johnson’s contributions to these developments – in terms of securing legislation and funds and actually planning and building the roads – were significant.

State Capitol Building

The Legislature authorized construction of the Nebraska State Capitol during Johnson’s tenure as state engineer. A Capitol Commission was organized and Johnson was appointed a member, in a capacity that Johnson would later refer to as a “watchdog” over the construction process and expenditure of state funds. Following the advice of Tom Kimbell, an Omaha architect who was hired as an adviser, the commission held a preliminary competition allowing all architects in Nebraska to submit plans for construction of the building. The winner was given the right to compete in the final competition with other architects from across the nation. The final award was made to Bertram Goodhue of New York.

After the award was made and plans submitted (and taxes were raised to pay for the building), Johnson spent considerable time making studies of the size and arrangement of the offices, Legislative chambers, the Supreme Court, and State Library within the building. During this process, he considered the function of the offices and their relationship with one another to maximize the efficiency of movement by employees between the offices with which they had frequent contact.

In 1922, as work progressed on the building, the contractor providing the limestone started shipping large amounts of material that did not conform to the original specifications (No. 1 Bedford Limestone with crush strength of no less than 8,000 lbs. per square inch). Some was No. 2 limestone, part of it No. 3 and part was below the lowest grade of less than 4,000 lbs./sq. in. Past experience had determined that the soft limestone would deteriorate fairly quickly in Nebraska’s climate and Johnson refused to approve the contractor’s claims for payment. However, he found that the limestone had been approved by the representative of the architect and the claim for payment had been approved by the clerk representing the architect at the building site.

In addition, certain other specifications had not been revised to meet with the Capitol Commission’s approval, such as the materials for casement windows. In some cases, the specifications were written such that a single company manufacturing certain items was the only one that could meet the specifications. During a discussion with the architect, Johnson asked if anyone was getting a commission for adopting the use of their equipment or materials for the project. His reply was, “Certainly, it’s common practice.” After discussing his concerns about the issue with the other members of the Capitol Commission, the commission chose not to pursue the matter.

Johnson then went to the Legislature with a joint resolution asking for an investigation into the practices of the architect and contractor. He filed a statement with 26 charges against the firms, and the Capitol Commission added two more charges. The results of the investigation and findings of a committee convened for that purpose were published in the House and Senate Journals for the 1923 session of the Legislature. The investigation’s resulted in significant cost savings for the State and the quality of the capitol building construction was enhanced.

However, while some of the stone that had been laid was removed and replaced, during subsequent changes extremely large mortar joints were made in the walls of the building. Johnson stated that these joints had been shown by experience to shrink in Nebraska’s climate as the mortar cured. Johnson was concerned that water would get into the joints and the freeze-thaw process would cause the mortar to spall, or crumble and fall out. His concerns went unheeded at the time.

Since nothing was done to correct the size of the joints, the State was subsequently faced with a continual task of refilling the joints over the decades after the building was completed. In fact, a 1995 inspection of the entire exterior surface of the Capitol was conducted by consultants, who determined that Nebraska’s seasonal temperature extremes and resulting freeze-thaw cycle had caused extensive movement and cracking in the stone building face and roof system sufficient to require major reconstruction of these critical building components. Johnson had warned of the inadequate joints during the construction process, but no corrective action was taken. Decades later, the need arose to repoint the mortar joints throughout most of the exterior of the building, a project that started in 1997.

Contract Work after Resigning from the State Engineer’s Position

Johnson took a three-month vacation to Spirit Lake, Iowa after leaving the state engineer’s position, one of the few real vacations he admitted to taking over his career. He then proceeded to organize the Economical Bridge Association, a company that built bridges and sold bridge material and lumber. His company built large bridges over the Platte River at Cozad and Gothenburg and was involved in construction of another Platte River bridge between Omaha and Plattsmouth.

The Omaha/Plattsmouth bridge was constructed on the basis that promoters of the bridge would take tolls until the cost of construction was paid and then the bridge would be turned over to the State of Nebraska without charge. The company also built two bridges over the Arkansas River in Ford County, Kan., plus another 22 steel bridges over tributaries to the Smoky Hill River in Ellsworth County, Kan.

Johnson sold the bridge company in 1928 and accepted a position with Blackmer Post, LeClede Christie and Evans and Howard in St. Louis. It was during this time that “we secured a law in the Missouri Legislature which was referred to as the basic law that was used for Senate File 310 in the Nebraska Legislature.” This law not only authorized the creation of districts and the construction of works in each district, but it also provided that a tax levy could be made sufficient to cover the cost of the preliminary engineering work. One of his first duties was to oversee engineering during the process of building a new sewer system in St. Louis using vitrified clay pipe. The stock market crash of 1929 caused the project to be delayed until the Public Works Administration was established and government funds were available to complete the project. By that time, Johnson was heavily involved in the development of the hydroelectric and irrigation projects in Nebraska and did not return to St. Louis.

War Plants and Ammunition Depots

Johnson played a significant role in attracting defense and munitions factories to Nebraska during World War II. In his own words:

“During the year of 1941 there were a large number of persons moving out of the State of Nebraska to other states to work on defense plants which were being located in these states. Mr. Burton Thompson, Mr. Howard Pratt and others requested me to go into the problem of securing some of these defense plants in Nebraska, especially one at Hastings for the purpose of stopping this migration. As we had a considerable amount of surplus power at that time, I was satisfied if some of these plants could be located in Nebraska, we would very materially increase revenues to our hydro districts without increasing costs. I did considerable work in 1941, in 1942 extending into 1943, to secure defense and war plants and a part of the aviation program for the State of Nebraska. This included all of the defense and war plants and aviation fields located in Nebraska by the government with the exception of the Bomber Plant at Omaha and the Lincoln Airbase. The only substantial help I had from anyone in Nebraska in securing these defense plants, war plants and this aviation program was Carl Marsh of McCook, Lloyd Thomas of Kearney, who helped with the aviation program, and Emil Placek of Wahoo, who assisted with the Mead Ordnance Plant. Senator Norris helped in Washington with all the programs in the state with the exception of the Hastings Navy Ammunition Depot. He was in the hospital during this period and was unable to help us.”

For most of 1941 — and with the blessing of CNPPID’s board of directors — Johnson devoted about half of his time to working on various defense projects, until the war started after the attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7. At that point, the plants were no longer referred to as “Defense Plants;” they became known as “War Plants.”

Johnson started by contacting Sen. Norris, who said he would do all he could to help located munitions plants in Nebraska. One of the primary factors Nebraska had in its favor was the recent completion of the hydropower system, which meant that plentiful and inexpensive power supplies would be available to the facilities. Working with Emil Placek of Wahoo and Sen. Norris, the first Army ammunition plant that was secured in Nebraska was located at Mead. Johnson had tried to have the plant located near Hastings where it could help alleviate the exodus of workers to other states’ military ammunition plants. However, the Army Corps of Engineers selected Mead because of its proximity to Omaha and the city’s surplus labor supply.

The Nebraska contingent also succeeded in attracting a second ordnance plant to a site near Grand Island which had ready access to sufficient water supplies for the plant. Johnson also worked on bringing “powder plants” to Fremont and Columbus, which ended up being built in other states after premature “local information leaks” about the prospective plants in each of the cities angered the military planners.

Johnson eventually was successful in bringing a War Plant — the Naval Ammunition Depot — to Hastings after working closely with several Naval officers in Washington. Among these was Chief of Ammunition Commander R.W. Holsinger, who was traveling by rail to various sites in states near Nebraska to review potential sites for ammunition plants. Johnson, in Washington at the time, contacted Cmdr. Holsinger on a Monday about the Hastings site, but was told the commander was leaving by train on Wednesday and could not change his travel plans unless an application for siting a plant was filed with his office by 9 o’clock Tuesday morning. Previously, Johnson had prepared plans for a chemical warfare plant at the site near Hastings. He worked quickly to adapt the plant to the Navy’s specifications and submitted the application on time the next morning.

Johnson then traveled to Grand Island to meet Cmdr. Holsinger’s train, drove him to the site near Hastings and eventually convinced the Naval officer that the site was perfectly suited for the Navy’s needs. Within two days of Cmdr. Holsinger’s visit, it was announced that an original allotment of $90 million would be made for constructing the ammunition plant at Hastings.

Securing these government expenditures in the state, which amounted to approximately $400 million, not only helped the state from the standpoint of bringing in additional buying power for its citizens, thus benefiting local merchants, but increased the revenues of the hydro districts and helped solidify their status during the early days of operation.

Military Aviation Fields in Nebraska

In the early 1940s, while Johnson was working to bring defense and war plants to Nebraska, he was approached by Sen. Norris to help with a request from municipal representatives from McCook and Kearney to attract Army Air Corps bases to Nebraska. He arranged for a meeting with Under Secretary of War Robert Patterson, who was instrumental in the mobilization of the armed forces preparatory to and during World War II. Johnson’s goal was to convince the under secretary that Nebraska was an ideal site for air bases, rather than expanding operations in the southern United States where weather was judged to be better for flight training.

Johnson was given 20 minutes with Patterson to state his case. He informed the under secretary that he had been studying the Army’s training regimen for pilots, which included “more good days for primary training in the southern states than there were in Nebraska and other northern states, and it was more economical to provide training in warm weather states where trainees could put in more time because better weather conditions and advance more rapidly.”

Johnson wrote in his memoirs:

“I told him that that the Army was making the same mistake they had previously made by training the fliers in southern Texas and Florida. The program they were following was to start out the trainee on making circles around the air field and later out across part of the country and then come back and land at the airport from which they had started. From the experience we had in training students at Lincoln (Johnson had established a flight school in Lincoln shortly after WWI), the students trained in that manner would soon learn that when they reached a certain point from the field at a certain altitude, all they had to do was pull back on the throttle and they would land at the right place, learning very little about making landings under different conditions. As all the flights were made in practically the same weather, they did not advance much in their training.”

He also pointed out that pilots trained in this manner and later assigned to fly airmail planes for the U.S. Post Office had a poor safety record and experienced many crashes because they had been trained to fly only in favorable weather conditions. When they encountered poor flying conditions, they were more likely to crash than if they had previous experience with inclement weather.

Johnson suggested that in an expanded training program, the trainees could start at southern airfields and when they advanced to better, faster airplanes, they could be trained to take off and land under different conditions typically experienced in Nebraska. They would also be able to fly from airfield to airfield in Nebraska, taking off and landing at different locations that would require the pilot to calculate and think for himself each time under different conditions.

At this point in the meeting, Patterson halted Johnson, rose from the table to summon some more Army officers, and had Johnson repeat the ideas and suggestion that he had just made. The 20-minute meeting turned into a three-hour meeting as Johnson made his case for locating air bases in Nebraska.

As a result, the Army expanded its training program to add major fields at Kearney, McCook, Harvard, Fairmont, Lincoln and Scottsbluff. Together with the ammunition plants and depots, the addition of the Army air fields in Nebraska brought greatly increased investments into Nebraska’s war-time economy.

Omaha Industrial Alcohol Plant

In January 1942, while Johnson was working to attract ammunition plants to Nebraska, he also stated that it was “evident that it was going to be necessary to very materially increase the (ethyl) alcohol production in the United States for war purposes.” The alcohol could be used for industrial purposes, including synthetic rubber manufacturing, and to blend with gasoline to produce a high-octane motor fuel. One of the incentives for increased production, according to Johnson, was the large stocks of corn and other grain that were in storage, either in bins or simply in piles on the ground.

With the Japanese having taken over much of the territory in the South Pacific where sugar cane production was prevalent and German submarines interfering with trade between the United States and Cuba, again where sugar cane was produced in abundance, alternate sources of crops to produce what is now commonly referred to as ethanol were needed. In addition, acquisition of rubber from sources in Southeast Asia, the main commercial source of latex for rubber making, had also been disrupted by the war.

Despite learning that the chemical division of General Motors Corporation had determined that only an additional 150 million gallons of ethyl alcohol per year would be sufficient, Johnson’s conversations with other industrial representatives, including the Rubber Reserve Board, led him to the conclusion that the government’s requirements would exceed 600 million gallons per year. Farm organizations in the country were anxious to help fill that need. He also surmised that, if alcohol plants were built to assist the war effort, they would be in place after the war ended to provide a market for surplus grain and help bolster crop prices.

A bill passed without dissent in the U.S. Senate in 1942 that would provide for an allocation of equipment and material to manufacture synthetic rubber from grain products. Although the bill was vetoed by President Roosevelt, he asked Congress to take no further action on the bill until a report by a specially appointed committee could be completed regarding the feasibility of using domestically produced alcohol in the process. Known as the Baruch Report, it subsequently recommended that plants be immediately constructed in the Midwest – near the primary areas for grain production — on navigable streams to manufacture alcohol from grain.

Subsequently, and after a conversation with the director of the War Production Board, Johnson revised one of five initial applications for alcohol plants in Nebraska to convert a former power plant in Omaha to the production of industrial alcohol. Within a week of learning that the board’s wanted to build just one, rather than five plants and combine all production into that single plant, Johnson prepared an application and a redesigned plan for a facility that was capable of producing 50,000 gallons of alcohol per day.

When the application was filed, he was told that the government would require changes to the plans necessary to facilitate production of 100,000 gallons per day. Within another week, Johnson revised and submitted his plans which were accepted by the board and approved by the President.

Authorization was received just one year and two days after the Johnson submitted his original request for an allocation to build an alcohol production plant. Using mostly second-hand materials, the plant was constructed and went on-line within one year of receiving final authorization.

It was the first time in the United States that industrial alcohol was made through a continuous process, starting with unloading the grain from rail cars and ending with placement of the alcohol in tank cars. The mash, or animal feed, that resulted from the process was also loaded into train cars for distribution to area producers. Another by-product of the process was corn oil, which was later marketed as Mazola Oil. Other uses included manufacture of a soap stock from the residue of the corn germ and malt syrup (300,000 lbs./day) which could be used to help alleviate the shortage of sugar for sweetener during the war.

The Omaha Alcohol Plant was one of the larger consumers of electricity generated at Nebraska’s hydroelectric plants. Immediately upon starting this plant, the demand charges of the hydros to the Nebraska Power Company – a private power company in Omaha until being purchased by the public power districts in 1946 — was increased an extra $5,000 per month or $60,000 per year (about $915,500 in 2016 dollars); in addition to the Districts being paid for the energy used which had previously been sold as surplus or dump power without demand charge, this one plant was worth $60,000 per year to the hydro districts from the day of its starting operation. The other war plants and air bases all helped in proportion to the power used.

Over the last six months the Omaha plant was operated for the government, it produced products at the lowest cost and at the most economical level of all alcohol plants in the United States.

Johnson later wrote that he testified before a Congressional Committee about the need to stabilize agriculture in the Midwest as part of a solid economic foundation:

“… I explained how we were sending out most of our raw materials and buying finishing materials. I also explained that to build up the maximum economy of our people, it was necessary to manufacture more of the things we need from the raw materials we produced. It was also necessary to take care of our surplus in an economical manner, and if the surplus was taken care of, the farmers could be allowed to raise all of the crops they wanted to raise without restriction, and the only control would be the amount of farm crops that would go into the manufacturing of alcohol for motor fuel. This should be controlled by Department of Agriculture, also the price that was to be received for alcohol for motor fuel should be controlled by the Department of Agriculture, so the manufacturers of alcohol would not be given a monopoly without control.”

Johnson was one of the principle early supporters of a movement – which would take many decades to coalesce – that advocated the construction of alcohol plants to produce industrial alcohol from agricultural products to power internal combustion engines. At the same time, the plants would benefit farmers and the rural economy by creating an alternative to government programs that reduced acres or paid subsidies to farmers to not grow crops. Even as early as the 1940s, his idea drew strong opposition from the oil interests which considered ethyl alcohol a threat to the industry’s motor fuel monopoly.

He sold his interest in the plant in 1948 after he organized an engineering company and entered into a contract with the government of Argentina to develop two rivers for hydroelectric power and irrigation.

Engineering Work in Argentina

Johnson was originally approached by a representative of the Argentine government to assist with the development of an alcohol plant – for many of the same reasons Johnson had enunciated – in 1946. Joel Soler, commercial attaché for the Argentine ambassador had heard Johnson’s testimony about the importance of industrial and agricultural production to a country’s, and its people’s, well-being. By September, Johnson had prepared plans and specifications for an alcohol plant similar to that which was operating in Omaha. At the time he presented his plans, he spoke with several government representatives about the development of their natural resources, including the development of hydropower, before they would be in a position to construct large industrial manufacturing plants. Argentina at the time imported most of its fuel, including coal, oil and gasoline, which made it difficult to operate manufacturing plants to compete with the countries that were supplying its fuel.

The next year, Johnson met with the head of a purchasing commission for Argentina in New York. The official informed Johnson that the country was ready to proceed with a five-year program that included development of certain natural resources, including hydropower and storage for irrigation projects.

In April 1947, Johnson traveled to Buenos Aires to meet with representatives from the Ministry of Industry and Commerce and with President Juan Peron. At the close of these meetings, an offer was extended for Johnson to assemble a team of engineers and move to Mendoza, Argentina. He was told that they would be able to choose any location that they wished along the east side of the Andes Mountains for development of water resources. After examining the area for three days, he selected the Mendoza and San Juan Rivers.

Johnson returned to the United States, where he resigned his position with CNPPID and began making preparations to build dams and hydroplants in Argentina. Eventually he formed a company of about 90 employees – some of whom had worked with him to build CNPPID’s project – and they set about doing all of the preliminary work necessary to build dams, storage reservoirs and hydroplants.

In addition to that work, his employees began investigating the possibility of developing other natural resources. During those investigations, they found deposits of coal, silver, copper, bentonite, phosphorus and all of the elements necessary to create high-grade cement.

However, due to political and economic instability in Argentina beginning in 1950, Johnson found it necessary to sell his share in the company he had organized to local interests and to return to the United States.

Purchase of Private Power Companies in Nebraska: Formation of Public Power Districts

Johnson’s biographer wrote that the early days of public power in Nebraska “… required a man with vision, as well as electrical and civil engineering experience, resourcefulness, and the knack for getting things done. He had all of those qualities. The greatest passion in his life was to bring low-cost electric power and effective irrigation to the people of Nebraska.”

His work to promote and develop the “Tri-County Project” was an outlet for his energies and served him well later in the development of the Nebraska Public Power System.

Johnson played an important role in the purchase of Nebraska’s private power companies by the state’s public power districts between 1937 and 1946.

At first, the hydropower districts (Platte Valley, Loup and Central (or “Tri-County”)) tried to market their electricity to the private power companies, but the private companies refused to pay a price that that would even equal the cost of production. The private companies, which had little interest in serving rural areas because of the lack of profit potential, had tried to prevent the formation and operation of the public power districts and were averse to doing anything that would help the public power districts succeed. However, a few minor sales contracts were finalized during these initial phases in 1938.

For reasons associated with the bond market and interest rates, the Federal Works Agency suggested that the hydropower districts organize a separate district for the purchase of the private power companies. The Consumers Public Power District was created in 1939 as a result of this suggestion. The property of the private power companies was gradually purchased by Consumers and transferred by a lease-purchase agreement to the public hydropower districts.

The operating agreement among the three hydropower districts set up the operations of the transmission systems belonging to the districts into a grid system known as the Nebraska Public Power System. The manager of each hydropower district made up the board of managers for NPPS and Johnson was chairman of the board. The function of the board was to jointly operate the transmission system, the power plants that had been purchased from the private companies, construction of additional facilities, and to arrange for power sales.

Formation of Rural Electrification Administration (REA) Districts

The Rural Electrification Act of 1936 provided federal loans for the installation of electrical distribution systems to serve isolated rural areas of the United States. The funding was channeled through cooperative electric power companies, most of which still exist today. The Act created the Rural Electrification Administration which oversaw implementation of the Act.

Johnson and others began working on organization of REA districts in Nebraska as soon as the Act was passed. At the time, he was spending most of his time in Washington to secure approval of CNPPID’s project. He gathered post road maps from each county, and maps showing the location of existing power lines from the Nebraska Railway Commission. With this information, he began to study the best way to lay out electric and transmission service for Nebraska’s REA districts. In this manner, he designed transmission systems for several REAs, including the systems in Platte, Lancaster and Polk counties. He also helped organize districts in a 12-county area in south-central Nebraska.

In the end, the rapid development of the REA districts was of tremendous value to the hydropower districts as there was almost immediately sufficient demand for the generation from the hydroelectric plants to serve the many rural farmsteads and ranches that were being added to the electric grid. The rapid growth in demand for power – particularly in rural Nebraska – contradicted the claims by the private power companies that the state would never need the additional power being provided by the hydropower districts. The swift construction of transmission facilities to deliver the power to farms, ranches and small towns reinforced Johnson’s steadfast belief that electricity would greatly improve the quality of life for all Nebraskans.

Robert E. Firth wrote in his book, “Public Power in Nebraska,” “No man is more important in the history of public power in Nebraska than George E. Johnson.” Indeed, he was among the giants in public power in Nebraska at the time.

Canaday Steam Plant

Upon returning to the United States after his time in Argentina, Johnson renewed his association with CNPPID and was named the District’s chief engineer in 1952. He was appointed manager of the Steam Division in 1957, which was created in preparation for building and operating the Canaday Steam Plant.

In the mid-1950s, it had become apparent that Nebraska needed additional generating facilities. Studies started in 1955 to investigate the construction of the natural-gas fired power plant southeast of Lexington and adjacent to CNPPID’s Supply Canal. The site next to the Supply Canal’s source of cooling water and the proximity to existing powerlines (although several would need to be upgraded) and natural gas pipelines, as well as the underlying soils, were judged optimal for construction.

Johnson was placed in charge of designing and constructing the plant, as well as training the personnel to operate the plant after its completion. He supervised construction of the 100-megawatt plant which went on-line in May 1958 to help meet the state’s growing demand for electricity.

The plant, one of the largest in Nebraska at the time, was finished ahead of schedule and cost about $16 million, $1 million less than had been estimated. These savings were realized largely because Johnson decided that it would be best not to hire a “prime contractor” as was the typical practice. Instead, at the age of 71, Johnson decided that he would assume these duties. He was responsible for selecting and coordinating 32 contractors and 40 separate contracts.

Before construction had even begun, 26 of the state’s rural electric districts had signed contracts to buy power generated at the power plant, a significant development in convincing the Rural Electric Administration to loan money for the plant’s construction.

Other Activities

Johnson was also interested in the potential for modern means of transportation, including the automobile and the airplane. In 1909, he was one of the first businessmen in Nebraska to buy an automobile to make traveling quicker and easier (and in doing so came to the realization that the state’s roads were in dire need of improvement). He was pleased with the first automobile he purchased, a Chalmers four-cylinder vehicle, because of its reliability and considered it a vast improvement over the horse-and-buggy mode of transportation that was common at the time. As with most early automobile owners, he was his own mechanic and steadfastly refused to allow anyone else to work on his car.

He learned to fly in 1926. He took flying lessons in Lincoln and, after making his first solo flight, he purchased a Lincoln Standard bi-plane. Shortly thereafter, he bought the aviation school where he had trained to fly, the same school at which Charles Lindbergh had learned to fly. Over the years, he would own and fly several airplanes, the last of which was a Travelair with an enclosed cabin and a 200-horsepower Wright Whirlwind engine, the same engine that Lindbergh had in the “Spirit of St. Louis” plane used to fly across the Atlantic Ocean.

Johnson became the first businessman in the state to regularly fly his own airplane for business purposes. As with his automobiles, he was always his own mechanic for the planes he used for business. No one else was allowed to tinker with his planes or their engines. In those early days, when there were few, if any, air fields near the places Johnson wished to travel for business, flying often meant landing where no airplane had previously landed, often in a farmer’s pasture.

The first airmail flight to Lincoln landed at his field, which was located on South 14th Street north of Lincoln Memorial Park Cemetery. He also built the first hangar on the site that is now the Lincoln Airport.

Johnson also took an interest in radio. The radio age was in its infancy and, as with all things technological, the new field of radio-wave communication piqued his interest. He built the most advanced amateur radio station in Nebraska in 1920 with the latest equipment available, all personally purchased from a radio supply store in Chicago. He erected two towers, one 80 feet tall and the other 60 feet in high with an antenna between them. He conducted many experiments with radio in the ensuing years and it was from this station that Governor Samuel McKelvie made the first radio broadcast by a governor of the state. In 1922-23, weather and farm market reports were being broadcast from the station for the Nebraska State Department of Agriculture.

Memberships

Besides being a member of the State Capitol Commission and the Federal Highway Advisory Board, Johnson was a member of a number of state and national electrical and civil engineering societies, the Society of American Military Engineers, the Nebraska State Water Conservation Congress, the International Board of Technical Engineers, and was a charter member of the Hastings Planning Commission. In 1961 the University of Nebraska Board of Regents presented Johnson with its highest non-academic honor for distinguished service – the Nebraska Builder Award – in recognition of his “conspicuously effective leadership in the fields of engineering and administration.”

Perhaps Johnson’s work in the engineering field is best summed up by comments he once wrote about natural resources and the people that depend on them. His comments summarized his convictions about the development of irrigation and public power projects in Nebraska:

“What happens to the land, the soil, the water and the minerals within the earth determines what happens to its people. It is upon these resources that men and nations must build. These are the foundations upon which our hopes and dreams for a future of prosperity and security are based.

“But everything depends upon how the job of developing such resources is done – whether it is for the welfare of all the people of the region or just for the financial benefit of a few individuals. The method followed determines whether these resources of the people will be exhausted and depleted by a few individuals seeking self-promotion or whether these resources are sustained, nourished, and made safe for the benefit of the present generation and of the generations to come. These natural resources are the heritage of all the people, and not the exclusive property of a few.”

Johnson applied these convictions to his work throughout his life, whether in neighboring states, on business travels to the eastern United States or in Argentina, but most of all, in Nebraska, his native land. In his biography, he said about the state:

“I have always loved Nebraska! It is a wide-open land with a big sky. It is a land where a strong man can use his muscles and stretch his brain. It is a land where a boy can dream the great American Dream and see it come true.

I have come to know it well. I have traveled it many times, border to border, by auto and airplane. I have farmed its soil and pioneered the use of surplus farm crops to make gasohol. I helped build its beautiful State Capitol building in Lincoln; and its highways, bridges, dams, canals and power plants.

Yes, Nebraska is a wonderful land of golden opportunities. Do you wonder why I love it so much?”

References/Sources of Information

Hamaker, Dr. Gene E. 1964. Irrigation Pioneers: A History of the Tri-County Project to 1935. Warp Publishing Company, Minden, Neb.

Johnson, George E., II. 1981. The Nebraskan. Anna Publishing, Inc., Winter Park, Fla.

Johnson, George E. 1967. Unpublished memoirs for The Central Nebraska Public Power and Irrigation District.

Conservation and Survey Division, Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources, University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Flat Water: A History of Nebraska and Its Water. Resource Report No. 12. March 1993.

Firth, Robert E. 1962. Public Power in Nebraska: A Report on State Ownership. University of Nebraska Press.